Running with the Brakes On: Is Muscle Coactivation Killing Your Running Economy?

Almost every runner is familiar with the feeling of 'heavy legs'. While often mistaken for a lack of fitness or strength, this sensation can stem from an internal tug-of-war between the body and its own momentum. To achieve optimal running economy, muscles need precisely timed, coordinated activation and relaxation patterns to enable fluid, dynamic movement. These activation sequences occur in milliseconds and are controlled by your nervous system. However, when a muscle contracts at the same time as its opposing muscle, either at the wrong time or too forcefully, you create excessive muscle coactivation.

Think of hamstrings contracting while the quadriceps try to straighten the leg. While some coactivation helps stabilize joints (1–3), excessive or poorly timed coactivation may increase unnecessary tension and energy cost. Over time, this can lead to slower times, reduced efficiency (4) and chronic frustration.

The Runner’s Paradox: Analyzing a Poor Running Economy

Our case study involves a middle-distance runner struggling with persistent hamstring issues. To identify the root cause, we performed a comprehensive gait analysis, measuring kinematics and electromyography (EMG) alongside metabolic testing.

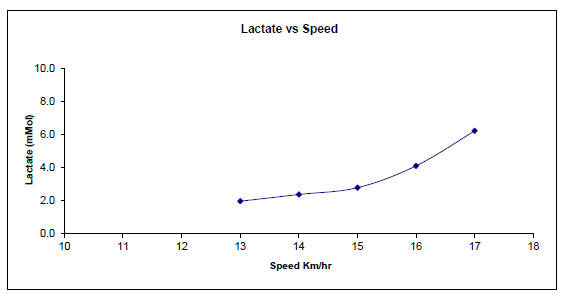

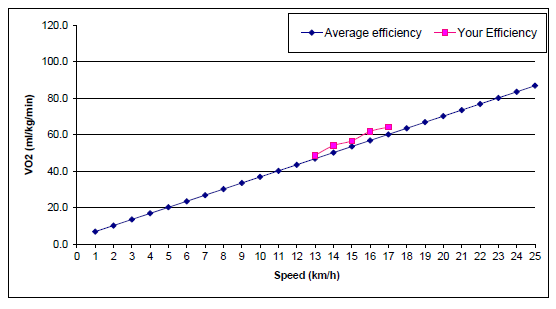

Specifically, we measured VO2 max and blood lactate during a progressively increasing-speed treadmill run. The metabolic results were surprising. With a VO2 max on the low end and a maximal blood lactate value of 6 mmol/L (Figure 1), the metabolic profile appeared submaximal. Nevertheless, I watched the athlete personally, and he was very close to, if not at, his limit. Despite kinematics suggesting an efficient running technique, his running economy (the oxygen cost of maintaining speed – see Figure 2) was remarkably poor.

Expert Insight: The Metabolic Ceiling

Ken Brunet, a highly experienced Clinical Exercise Physiologist and owner of the Peak Centre for Human Performance, explains the metabolic data in context:

"For an athlete of this calibre, you would expect to see higher lactates as they reach peak velocities. Seeing a ceiling at 6 mmol/L (Figure 2) alongside such a high respiratory effort suggests a potential dual constraint. While a neuromuscular bottleneck may have prevented a true maximum effort, we also must consider the metabolic fuel source. If glycogen stores were depleted, the athlete would not be able to drive the anaerobic system to its full potential."

Symmetry vs Stability: The Pelvic “Whip” Impacts Running Economy

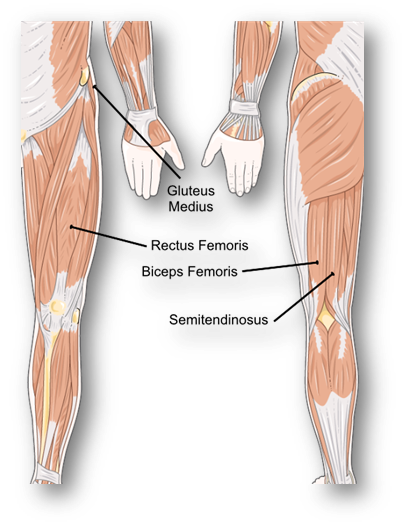

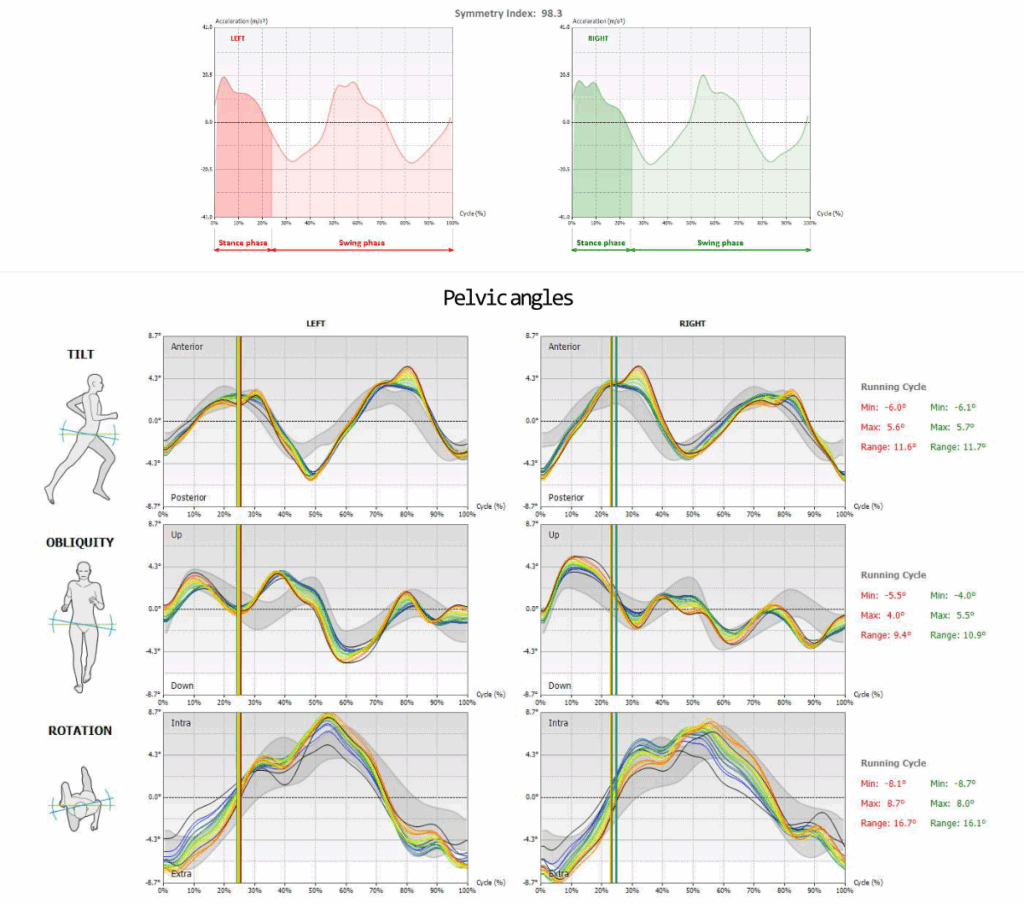

Gait analysis showed near-perfect symmetry (98%) in stride metrics and propulsion. Vertical acceleration (the rate at which the body moves up and down) was low, and transitions from heel strike to toe-off were smooth. On paper, he looked efficient; however, a red flag indicated something was wrong. We found signs of right-sided pelvis instability (Figure 3) during the stance phase, suggesting a lurking biomechanical issue (5).

Figure 3. Gait analysis results showing vertical acceleration and pelvic angles while running.

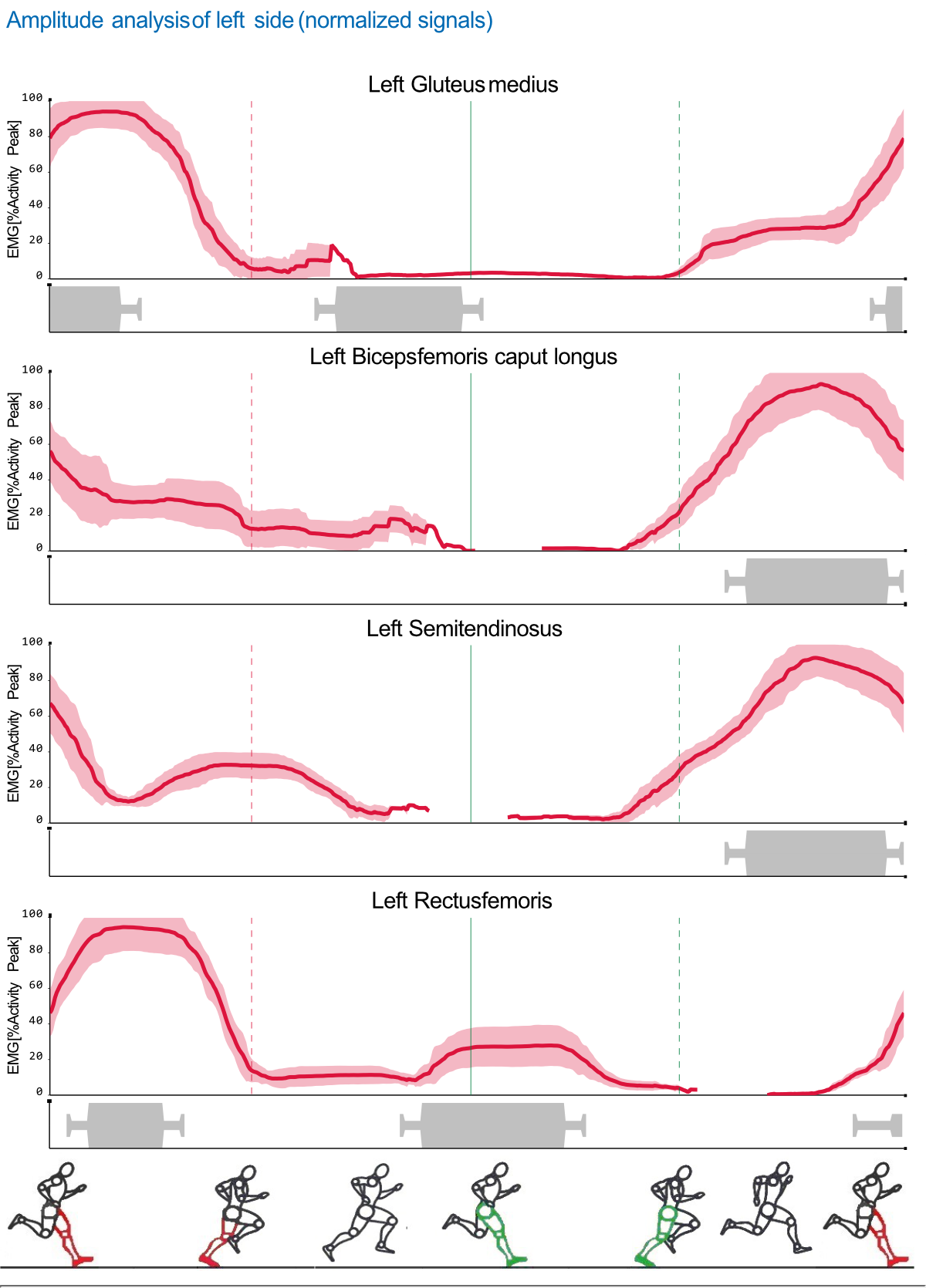

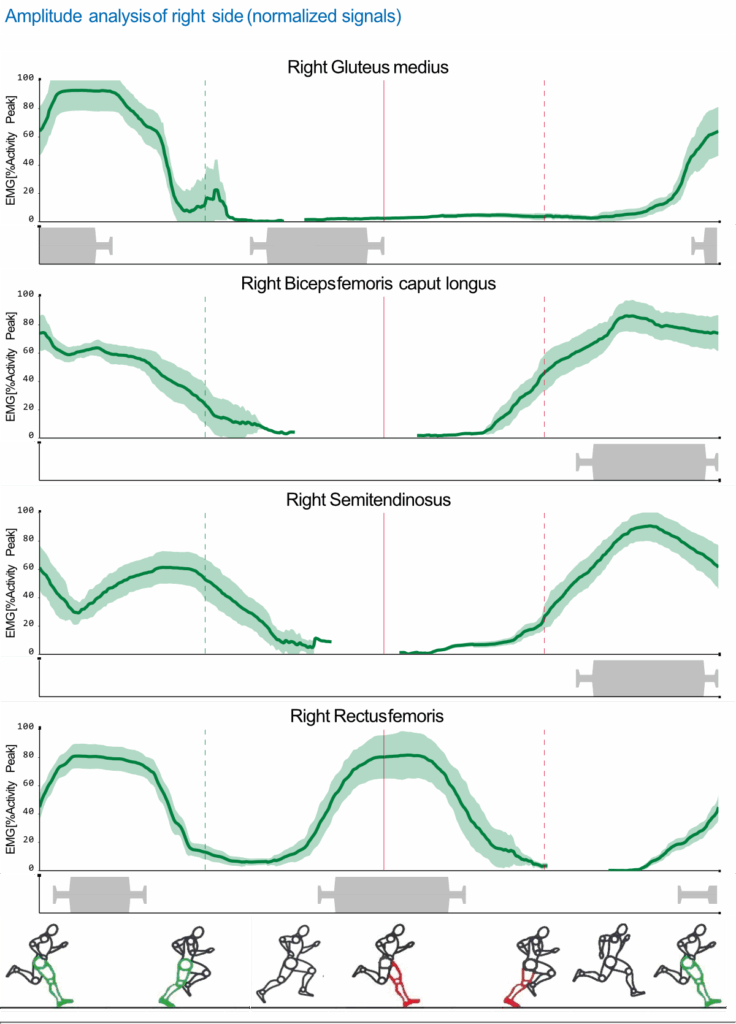

Then came the “smoking gun”, the EMG results. We examined the gluteus medius, rectus femoris, and the hamstrings (semitendinosus and biceps femoris) to examine muscle timing during the running stride (Figure 4).

For efficient running, the hamstrings should be relatively “quiet” for most of the swing phase and then fire in a fast burst just before and into heel strike to stabilize the knee and control extensions (1–3). The rectus femoris, gluteus maximus, and other hip and ankle muscles then contribute to forward propulsion (4). Figures 5 and 6 show that the right hamstring remained active longer and at a high level during the stance and swing phases.

The Neuromuscular Ceiling: Why An Over-Active Hamstring Limits Running Economy

We discovered a clear issue: muscle coactivation between the hamstrings and quadriceps was creating a “neuromuscular ceiling”. This ineffective timing likely increased energy demand and stress on the hamstrings. It is like driving a car with the parking brake on: poor fuel mileage and capped power output.

Expert Corner: The Coactivation Index and Running Economy

It is important to note that coactivation isn't always "bad." In fact, well-timed coactivation is essential for high-performance running. This creates joint stiffness in the leg for efficient force transfer at ground contact. The issue is neuromuscular timing. While "stiffness" at impact improves running economy, mal-timed or sustained coactivation during the propulsion phase acts as a brake, increasing metabolic stress. Every watt of power generated by the Rectus Femoris must overcome the "braking force" of a non-relaxed hamstring, while the hamstring tries to resist the more powerful Rectus Femoris. This could explain why the RQ (see Appendix) is high, but lactate is low (velocity is limited).

CWT: The Secret Weapon

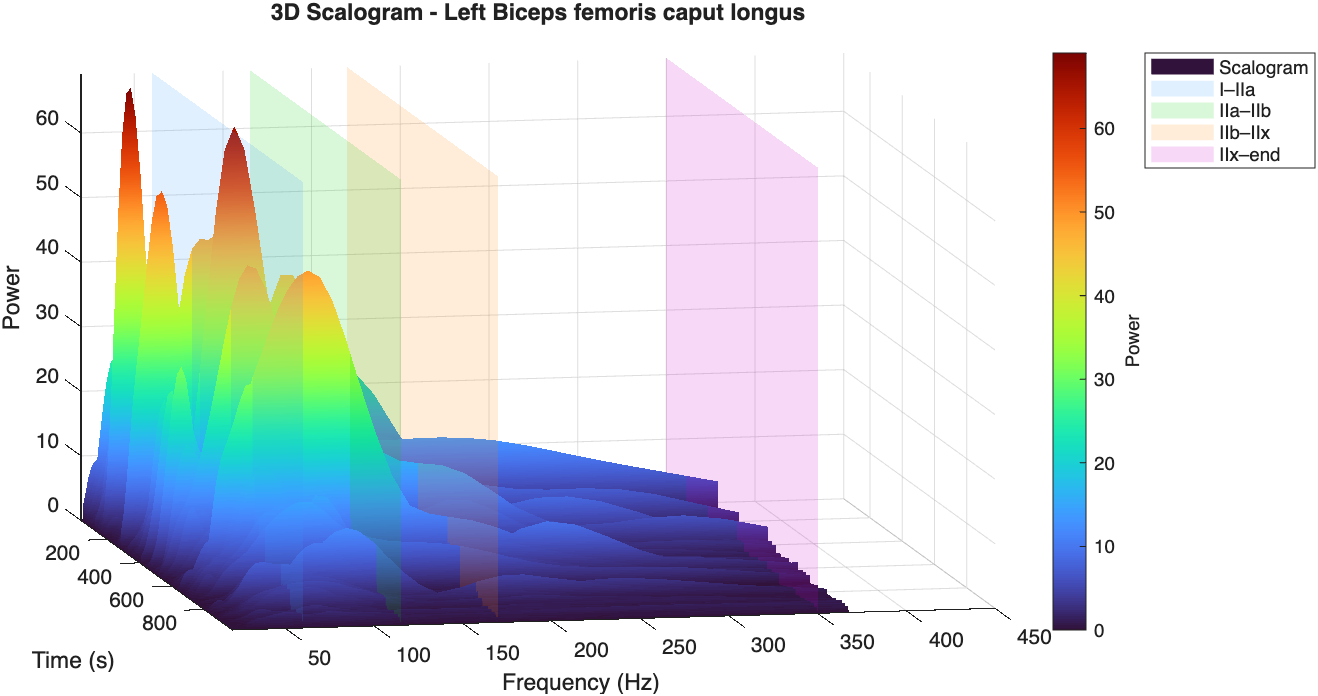

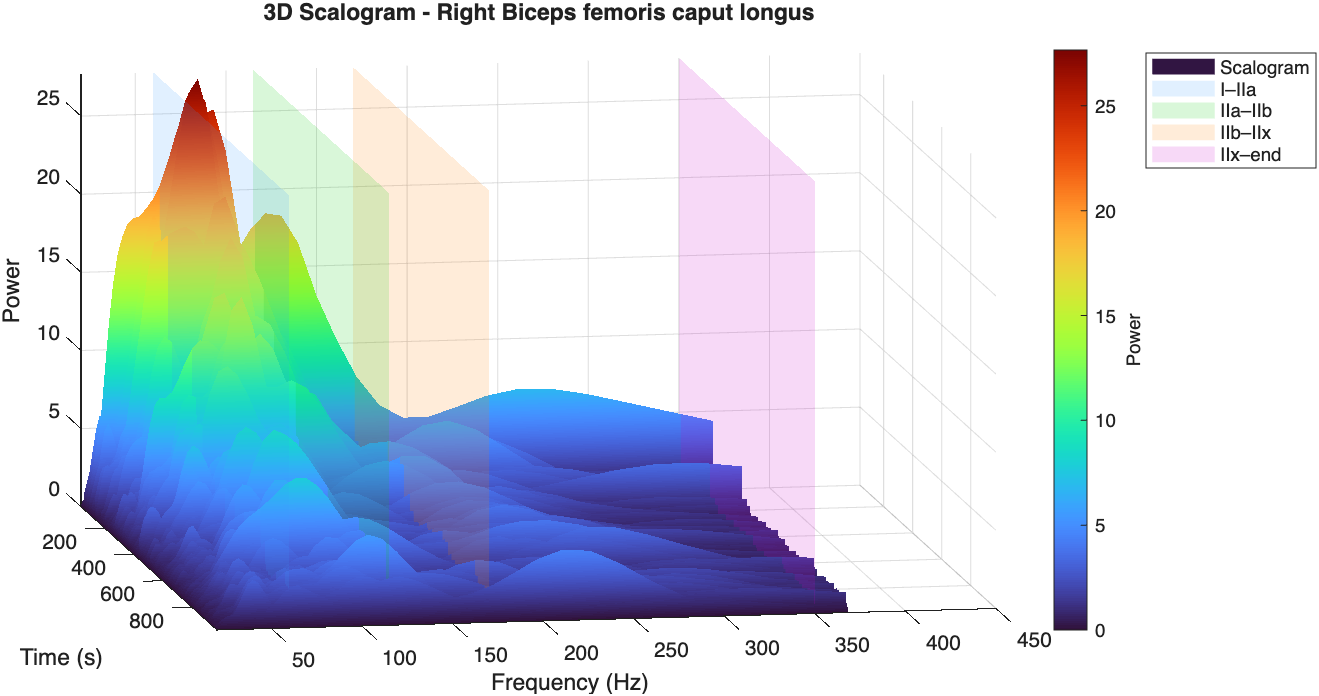

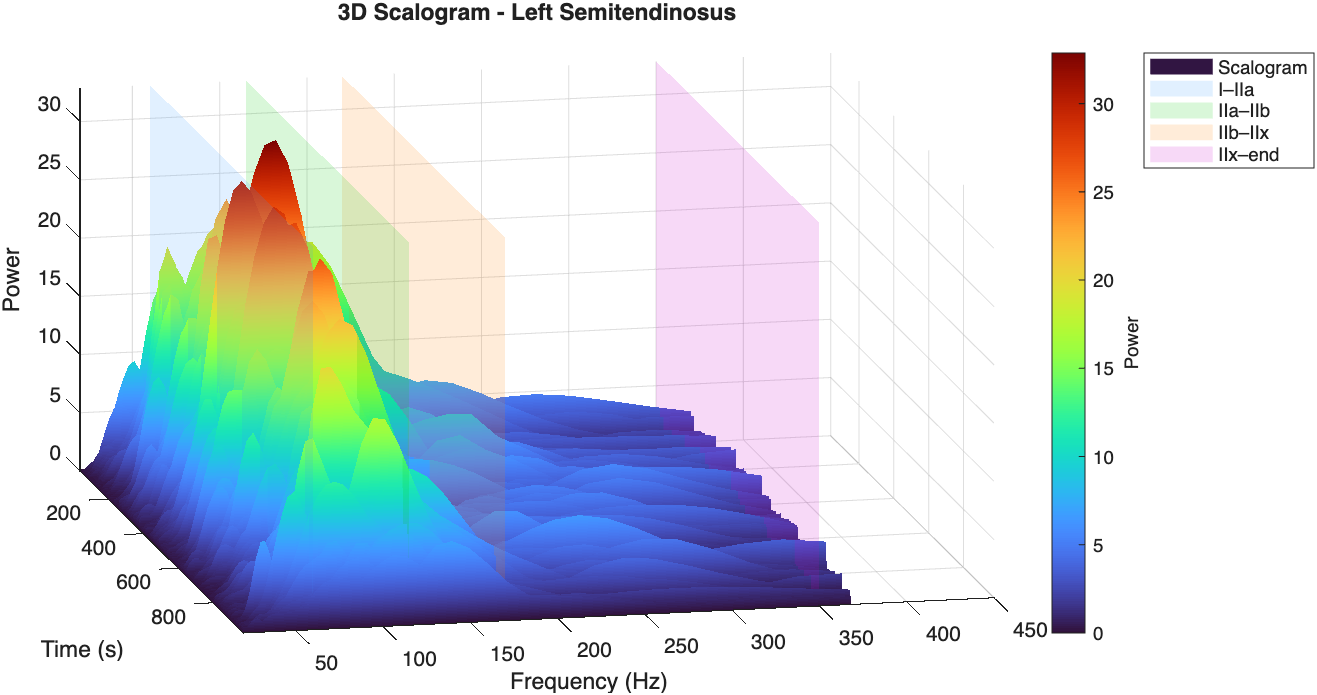

We used a technique called Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) to break down the EMG signal and visualize muscle recruitment patterns throughout the test (Figure 7). Special thanks to Dr. Victor Chan (Celestra Health Systems / University of Ottawa / Google Scholar), whose expertise in EMG and muscle fatigue was instrumental in interpreting these findings.

A progressive decrease in CWT magnitude across the frequency spectrum was observed in the right hamstring group, consistent with neuromuscular offloading or de-recruitment. Because this pattern was absent in the rectus femoris, gluteus medius, and contralateral hamstrings, the data suggest an issue with the right hamstrings rather than central fatigue factors.

Inhibition and Instability

This inhibition can contribute to the front-to-back “pelvic whip” motion detected by the gait analysis (5). As the hamstrings shut down, it is conceivable that the gluteus maximus and medius compensated by trying to share the load, although this is hypothetical since we did not measure gluteus maximus activity. This potential transfer of force may increase strain on the hip joint and the muscles surrounding it. Consequently, this internal force tug-of-likely created a biomechanical tax, contributing to reduced running economy and lower VO2 and lactate values.

The Fix: Releasing the Brakes to Improve Running Economy

Improving running economy isn't always about logging more miles or doing heavier squats and lunges. Strengthening a muscle that fires at the wrong time in isolation may simply increase the brake's tension. Instead, the goal is to focus on improving neuromuscular coordination as this has been associated with improved running economy (6) :

The "Push, Don't Pull" Cue:

Shift from “pull through the stride using your glutes” or “clawing the ground” to "pushing the ground away”. This can work to maximize reciprocal inhibition (expert callout) to naturally quiet the hamstring and encourage a properly oriented push phase.

A-Switches:

Rapid, rhythmic leg switches teach the brain to snap the leg into place just before contact, without holding tension throughout the swing. This “switches” the firing patterns in the thigh from drive to recovery.

Wicket Runs:

Use mini hurdles to train a quick, vertical foot strike under the center of mass, to reinforce a brief, powerful hamstring contraction followed immediately by relaxation.

Expert Corner: The "Push" cue taps into reciprocal inhibition, where activation of one muscle group helps reduce activity in its opposite pair, even though this reflex is more complex in humans than simple textbook diagrams suggest (7). By focusing on the Quad/Glute push, we are "hacking" the nervous system's strongest pathway to force the hamstring to release its grip.

Once excessive coactivation has been reduced and timing improved, focus on hamstring strengthening. Including eccentric and isometric strengthening at key knee angles should help to bring everything back into balance.

The Chicken or the Egg: Pelvis vs. Hamstring

It is difficult to determine whether the coactivation caused the pelvis instability or whether the instability triggered the guarding activity in the thigh. In practice, these factors often interact and reinforce each other. This underscores the benefit of baseline testing. Without knowing what it was like before the hamstrings became an issue, it can be difficult to narrow down the initial cause. Regardless of the origin, tackling improper muscle coactivation and timing early in the process makes sense. Only by improving the neuromuscular timing can we effectively transition to conditioning exercises that strengthen the entire chain.

Getting to the Finish Line

If you are training harder but moving more slowly, it may not be a fitness problem; you could have an efficiency leak that leads to poor running economy. By releasing the internal brakes and teaching your muscles to fire optimally, you don’t just improve running economy, you effectively remove a governor from your metabolic engine and give yourself the chance to express your true performance. Reducing excessive coactivation and optimizing timing not only improves running economy but may also lower stress on the hamstrings and decrease injury risk.

About the Author: Mike Croskery, M.Sc. HK (Biomechanics), CSEP-CEP

Mike Croskery is a Clinical Exercise Physiologist and CSEP High Performance Specialist™ with nearly 30 years of experience helping people from diverse populations improve their health, fitness, and performance. Mike’s true specialty lies in solving complex individual issues—whether they affect a runner's economy or a patient’s health in the context of chronic disease.

After years of field experience with elite athletes, first responders, and fitness and health enthusiasts, Mike earned his Master’s in Human Kinetics (Biomechanics), focusing his research on the practical use of surface EMG and force measurement combined with motion capture technology. Today, he applies those advanced diagnostic tools to a wide range of clients, including those managing cardiovascular, metabolic, and neuromuscular conditions. Mike’s unique approach blends academic research with 30 years of hands-on experience to help every individual—from the Olympian to the individual with chronic health concerns—move better and live healthier.

Are you interested in reading more about training?

Have you ever stood in the gym and felt overwhelmed by the next steps in your quest to build muscle and strength? In fact, you’re not alone if it feels like cracking a complex code to design a weight training routine that works. Consequently, common questions can bounce around in your head, such as: How many sets? What reps? Which exercises actually work? Additionally, how often should I even train?

Lactic Acid and Fat Burning: Optimize Workouts for Max Fat Loss

You’ve just finished your aerobic workout, you’re breathing hard and heavy, and your legs are weak and are burning like they're on fire. ‘That fat is going to be burned up like crazy,’ you think to yourself. However, what you might not know is that you may have just sabotaged your fat-burning quest. Specifically, generating high lactic acid levels from your hard workout.

References

- Moore IS, Jones AM, Dixon SJ. Relationship between metabolic cost and muscular coactivation across running speeds. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(6):671–6.

- Tam N, Santos-Concejero J, Coetzee DR, Noakes TD, Tucker R. Muscle co-activation and its influence on running performance and risk of injury in elite Kenyan runners. J Sports Sci. 2017;35(2):175–81.

- Kellis E, Zafeiridis A, Amiridis IG. Muscle Coactivation Before and After the Impact Phase of Running Following Isokinetic Fatigue. J Athl Train. 2011;46(1):11–9.

- Lenhart R, Thelen D, Heiderscheit B. Hip Muscle Loads During Running at Various Step Rates. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(10):766-A4.

- Badrinath K, Crowther RG, Lovell GA. Neuromuscular Inhibition, Hamstring Strain Injury, and Rehabilitation: A Review. Journal of postgraduate medicine, education and research. 2022;56(4):179–84.

- Bonacci J, Chapman A, Blanch P, Vicenzino B. Neuromuscular Adaptations to Training, Injury and Passive Interventions: Implications for Running Economy. Sports medicine (Auckland). 2009;39(11):903–21.

- Hamm K, Alexander CM. Challenging presumptions: Is reciprocal inhibition truly reciprocal? A study of reciprocal inhibition between knee extensors and flexors in humans. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):388–93.