Revealing Knee Replacement Exercises to Solve Muscles that Struggle

Stop guessing, your knee replacement exercises may be missing a muscle!

Using a rigorous EMG analysis, we uncover the muscle compensation patterns actually happening after a total knee replacement. Case studies reveal that your hamstrings and overlooked inner quad (Vastus Medialis) are likely overworking during standard knee replacement exercises like squats, signaling hidden weakness and instability. This article shows you the exact science-based exercises you need to stop compensating and build a stronger, more stable knee joint.

By Mike Croskery, M.Sc. HK (Biomechanics), Clinical Exercise Physiologist

For years, many knee replacement exercises have focused on 'waking up the quads.' This is often achieved through movements such as squats, leg extensions, and straight-leg raises. Accordingly, there's a good reason for this: studies show that patients who strengthen their quadriceps tend to have better outcomes after surgery (5,14).

However, a strong recovery isn’t just about targeting the quads. Recent research and clinical case studies suggest that the hamstrings (17,18)—specifically, the biceps femoris—also play a crucial role in determining the type of knee replacement exercises chosen. Unfortunately, this approach may often be overlooked and underestimated in rehabilitation.

With hundreds of thousands of knee replacements performed annually (1,3), it's essential to have a comprehensive rehabilitation plan. To help fill this knowledge gap, and from my own perspective as a clinical exercise physiologist specializing in biomechanics with experience in working with clients through this procedure, I looked at the muscle activation post-knee replacement of three thigh muscles in three different knees that underwent total knee arthroplasty.

Our Case Study: Examining Knee Replacement Exercises

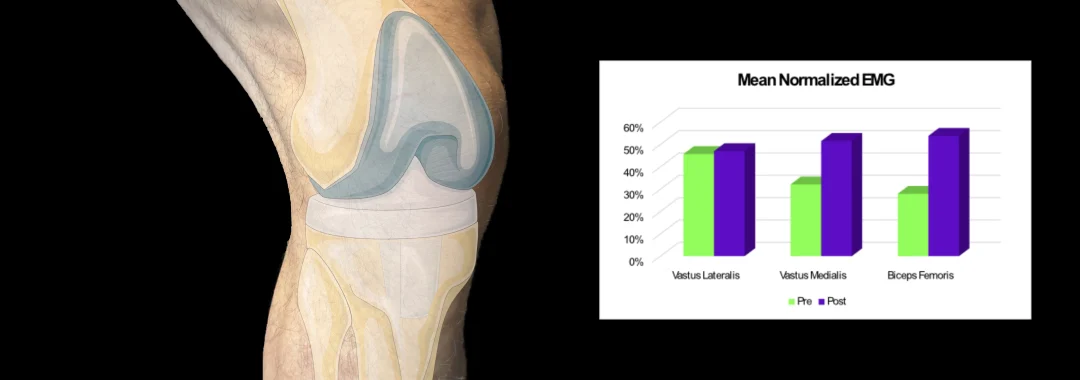

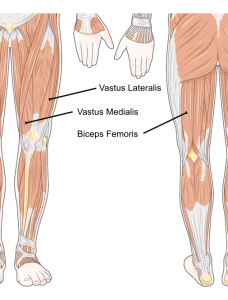

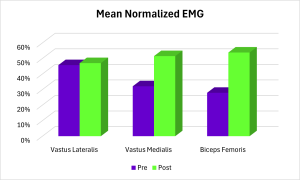

Our study looked at three key muscles in the leg. The vastus lateralis and vastus medialis, located at the front of the thigh, and the biceps femoris, located at the back. What we found was that after knee replacement, both the biceps femoris and vastus medialis were significantly more active than they were before surgery during two knee replacement exercises: the bodyweight squat and step up.

Interestingly, this increased activity might signal a potential compensation or instability issue after surgery. However, understanding why this happens—and what you can do about it—is the key to a quicker and more complete recovery. First, let's examine the anatomy of these muscles and understand how they contribute to knee strength.

Anatomy of the Thigh Muscles and Knee Function

- The biceps femoris (BF) is a major muscle in the hamstring group, and it's located at the back of the thigh. Its main jobs are to bend the knee and extend the hip. It also helps stabilize the lower leg.

- The vastus medialis (VM) is a quadriceps muscle on the inner thigh and is shaped like a teardrop. While its main job is to straighten the knee, it also helps to align and stabilize the kneecap. As a result, several studies have focused on strengthening the VM to help with knee pain (2,4,10).

- The vastus lateralis (VL) is a large muscle on the outer part of the upper thigh. It helps straighten the knee. It also stabilizes both the kneecap and the entire knee joint.

Altogether, these three muscles are fundamental for the force, power, and stability your leg needs.

How We Measured Muscle Activation During Knee Replacement Exercises

To understand how muscles recover post-surgery, we studied three knees from two patients who had a total knee replacement. First, we assessed the three muscles before surgery and then again between 3 and 7 months after surgery. All three knees had a normal range of motion at the time of reassessment. However, both patients reported constant pain in the back of the knee during specific knee replacement exercises and movements.

To get a precise understanding of muscle function, we used electromyography (EMG) analysis. The EMG signal measures how your nervous system activates muscles. We looked at muscle activity during four to seven repetitions of two common knee replacement exercises: the bodyweight squat and the step-up.

It's All in the Exercise Comparison

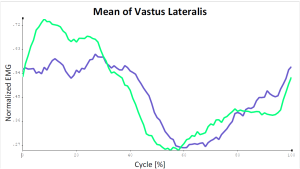

We performed these exercises both pre- and post-knee replacement. Then, we compared the EMG signals to the muscle activity recorded during the step-up. We used the step-up as our benchmark because it isolates each leg, allowing us to focus on individual movements. This provides a more consistent measurement than a squat, which can cause changes in muscle activation between legs due to subtle weight shifts.

Since raw EMG values can differ between people, we "normalized" the data. As such, this scientific process compares the EMG value to a standard. In our case, the standard was the step-up. Normalizing the signal helps us accurately see how hard the muscles are truly working and how the brain is using the relative capacity of the muscle. This is then compared to our simple, everyday movement, climbing stairs.

The Unseen Struggle: EMG Insights into Muscle Activation during Post-Knee Replacement Exercises

Our analysis revealed several interesting findings regarding muscle activation while performing post-knee replacement exercises.

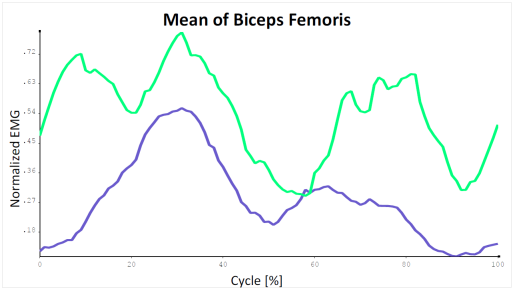

First, the biceps femoris appeared to work significantly harder after surgery to perform the same relative movement. This increase in muscle activation could be due to some form of compensation. It could be behaving this way due to specific muscle weakness or because it is trying to make up for weakness in the quadriceps. Because standard rehab often focuses on knee extension, the hamstrings can be overlooked or not trained intensely enough. This can leave them weak and overworked.

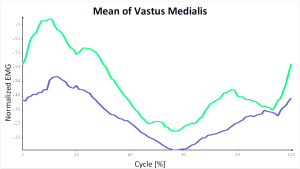

Second, the vastus medialis also showed higher activity after surgery. Again, this is likely due to the muscle needing to work relatively harder to stabilize the new joint. This finding suggests that a holistic rehab approach is necessary. Likewise, such an approach should not just focus on raw quad strength. It should also focus on the subtle but vital function of the vastus medialis.

Below, you can see the average muscle response before (purple) and after (green) total knee replacement while performing the knee replacement exercises (squat and step-up).

The EMG Revelation: Muscle Response in Knee Replacement Exercises

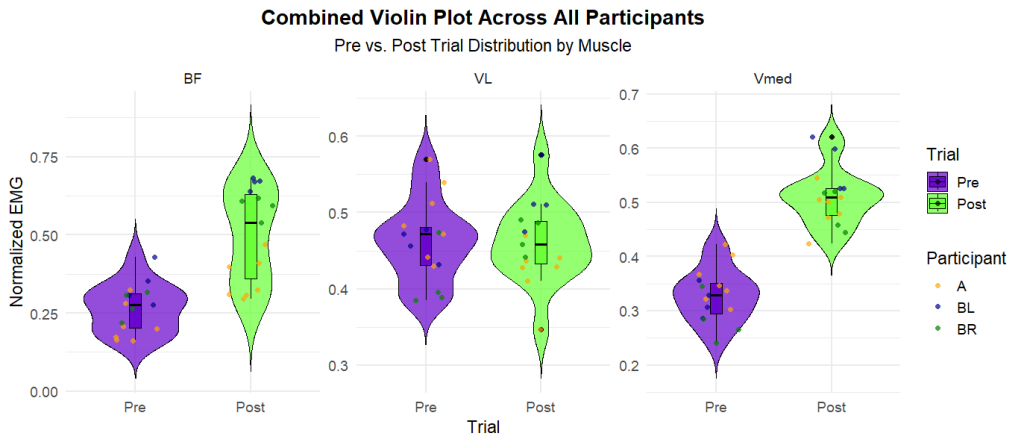

While averages are helpful, the violin plot below helps us understand the individual differences in the data. Think of it as a heatmap for the data, showing where most of the results are clustered for each muscle before and after surgery.

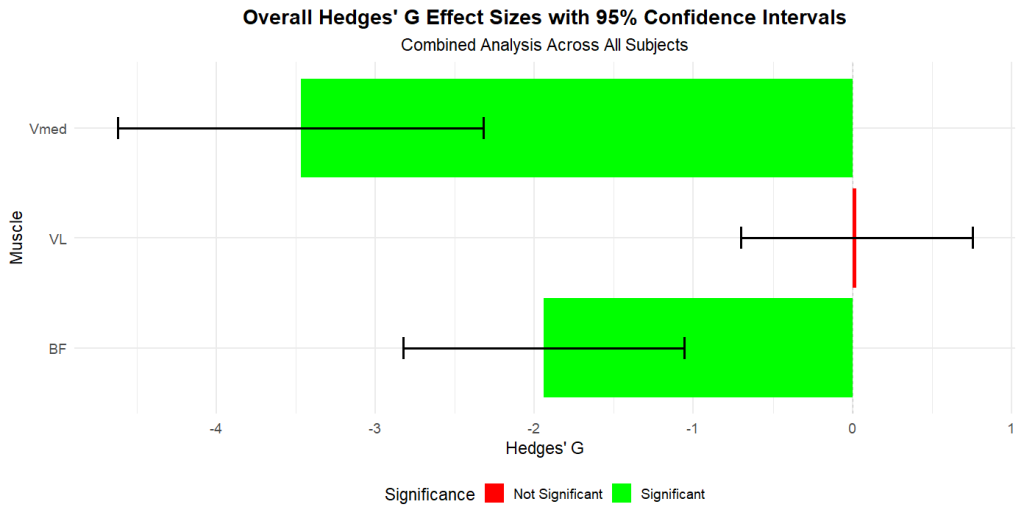

Interpreting the EMG Data: Effect Size & Confidence

To find a more precise answer, we used a statistical measure known as effect size (7). This helps us know if the differences are meaningful in the real-world context of muscle activation post-knee replacement exercises.

For example, a general guideline for knowing if there are meaningful differences is as follows(16):

- Small: under 0.34

- Large: over 0.65

- Very Large: over 1.2

For both the biceps femoris and vastus medialis, we saw a significant difference in muscle activation. Whereas the vastus lateralis showed only a minor change. We are also confident that these differences are not due to chance, as the confidence intervals (represented by the black range bars) do not cross the zero line (6).

Important note: Also, keep in mind that these are just three case studies. Individual results are often highly unique to that person. These results may not apply to a larger population.

What Does Increased Muscle Activation Post-Knee Replacement Mean for Recovery?

To understand this, let's review what an EMG signal is and what it is not. EMG measures the signal sent from the brain to the muscle, and it shows how hard the brain is "telling" the muscle to contract. It does not directly measure strength.

However, the neural signal is linked to the force being produced. For example, a weaker muscle needs a higher neural signal to create the same force as a stronger one (20).

Therefore, the increased activation we saw suggests these two muscles require a stronger signal after a knee replacement to perform the same movements. The most likely reason is that these muscles have become comparatively weaker after surgery. This, combined with a new joint shape and muscle damage, may lead to a less efficient system.

This increased contraction between opposing muscles is called co-activation. After a knee replacement, the nervous system often increases co-activation as a protective response to stabilize the new joint (11,19). This is a normal reaction.

However, if a muscle (such as the biceps femoris) is weaker, it will need a stronger signal to help stabilize the joint. Ultimately, this can create imbalances, making a full recovery more difficult.

Phase 1: Your Pre-Surgery Plan ("Prehab")

The first step to a quick recovery happens before the actual surgery takes place. As a result, this becomes your pre-surgery plan, also known as "prehab." The goal is clear: to strengthen your leg muscles as much as you can. Accordingly, research supports this approach as it can significantly improve your recovery after surgery (9,21).

Think of it as building a strength "reserve." Having stronger muscles gives you a critical buffer as you begin your recovery.

In this phase, focus on building strength in the front and back of your thighs. Include these knee replacement exercises:

- For your quads: Add exercises like leg extensions, reverse lunges, and leg presses. Be sure to choose movements that don't cause extra pain and that you feel comfortable with.

- For your hamstrings: Include exercises such as hamstring curls or stiff-leg deadlifts. As a result, this will strengthen the back of your legs.

Also, don't forget the rest of your leg! Your calves and hip muscles are crucial for the proper overall functioning of your leg. Be sure to include them in your routine.

Suggested Routine:

- Beginners: Focus on one or two exercises for the front and back of the thigh. Plan to do 2–3 sets of 10–15 repetitions for each.

- Advanced Lifters: You can increase your workout volume over time. Ultimately, adding more leg exercises and sets to your workout. However, ensure it doesn't worsen any existing knee pain.

Important Tip: You may also want to consult a physiotherapist or exercise specialist, as this can ensure you are on the right track. For more details on designing a workout plan, read the article "Designing a Weight Training Routine."

Phase 2: The Post-Surgery Knee Replacement Exercises ("Rehab")

At first, your rehabilitation phase should be guided by a professional. For instance, you will most likely be given a list of a variety of knee replacement exercises. These will strengthen your quads, hamstrings, and calves. Always follow your healthcare professional's advice on when to start. In the meantime, do not rely only on your pre-op training; consistency is the key to progress.

Once you get the all-clear, it's time to apply what we learned from our case studies. To accelerate your recovery and target those often-overlooked muscles, incorporate these targeted exercises into your routine accordingly.

- Start with your hamstrings: Begin your training sessions by focusing on the hamstrings, including the biceps femoris. Rehabilitation exercises, such as a variety of leg curls and stiff-legged deadlifts, can be beneficial for your knee recovery.

Remember, your pre-surgery training will help you get started early. However, the benefits won't last long if you stop exercising (12,21). Now is not the time to quit! Start slow and gradually build up your tolerance. Specifically, adjust to any initial or ongoing limitations.

The Long-Term Outlook After Your New Knee Joint

As we've seen, a successful knee replacement recovery isn't just about strengthening the quads. By incorporating targeted hamstring exercises and focusing on the roles of the biceps femoris and vastus medialis, you can adopt a more comprehensive approach.

Listen to your body and be consistent with your exercises. Although it takes time, you will ultimately enjoy the results of all your hard work and time invested. This focused approach can not only speed up recovery from a knee replacement but also ensure a stronger, more stable knee for years to come.

Learn about how you can assess your risk for ACL injury by examining muscle activation timing...

Concerned about ACL injury risk? This ACL injury risk assessment utilizes advanced technology to help athletes prevent re-injury & return stronger.

Learn about using EMG to select exercises for your biceps...

Our EMG study reveals the best biceps exercises for the long and short heads and how to maximize activation for optimal gains.

Best Biceps Exercises for the Long and Short Heads: An EMG Study

Learn more about assessing knee stability using drop jumps...

Uncover hidden risks in using a drop jump test for ACL recovery. Learn why drop height & pelvis kinematics are crucial to assess return-to-play.

Assessing Readiness: The Hidden Dangers of Drop Jump Tests in Injury Recovery

References and Scientific Literature

- American College of Rheumatology. Joint Replacement Surgery. Available from: https://rheumatology.org/patients/joint-replacement-surgery

- Armagan, O, Ayik, B, and Bakilan, F. Comparison of open and closed kinetic chain exercises on vastus medialis and vastus medialis oblique in patellofemoral pain syndrome: A randomized, single-blinded, prospective study. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 71: 216–225, 2025.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. CJRR annual report: Hip and knee replacements in Canada, 2019–2020. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/cjrr-annual-report-hip-and-knee-replacements-in-canada-2019-2020

- Farzam Farahmand, Seyyed Hosein Hoseini, and Mohamad Mahdi Seifi. Determining the Optimum Training Conditions for Selective Strengthening of Vastus Medialis Oblique Muscle over Vastus Lateralis through Using Musculoskeletal Modeling. Biyumikānīk-i varzishī 2: 65–76, 2016.

- Furu, M, Ito, H, Nishikawa, T, et al. Quadriceps strength affects patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Science 21: 38–43, 2016.

- Gardner, MJ and Altman, DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. BMJ 292: 746–750, 1986.

- Goulet-Pelletier, J-C and Cousineau, D. A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, Part I: The Cohen’s d family. Quant Method Psychol 14: 242–265, 2018.Available from: http://www.tqmp.org/RegularArticles/vol14-4/p242

- Hosseini, SH and Farahmand, F. Is it truly impossible to strengthen the vastus medialis in isolation from the entire quadriceps muscle group? Heliyon 10: e41012, 2024.

- Jørgensen, SL, Kierkegaard, S, Bohn, MB, Aagaard, P, and Mechlenburg, I. Effects of Resistance Training Prior to Total Hip or Knee Replacement on Post-operative Recovery in Functional Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Sports Act Living 4: 924307, 2022.

- Kim, H. Effects of Selective Training on the Vastus Medialis Oblique in Patients with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science 14: 91–101, 2025.Available from: http://www.jptrs.org/journal/view.html?doi=10.14474/ptrs.2025.14.1.91

- Latash, ML. Muscle coactivation: definitions, mechanisms, and functions. J Neurophysiol 120: 88–104, 2018.

- McKay, C, Prapavessis, H, and Doherty, T. The effect of a prehabilitation exercise program on quadriceps strength for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled pilot study. PM R 4: 647–56, 2012.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22698852

- Mirzabeigi, E, Jordan, C, Gronley, JK, Rockowitz, NL, and Perry, J. Isolation of the Vastus Medialis Oblique Muscle During Exercise. Am J Sports Med 27: 50–53, 1999.

- Petterson, SC, Mizner, RL, Stevens, JE, et al. Improved function from progressive strengthening interventions after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial with an imbedded prospective cohort. Arthritis Rheum 61: 174–183, 2009.

- Polawski, M, Zyznawska, J, and Frankowski, G. Optimization of the position for isometric exercise to strengthen the vastus medialis oblique muscle based on surface electromyography tests: an observational study. Physiotherapy Review 27: 19–30, 2023.

- Schober, P, Mascha, EJ, and Vetter, TR. Statistics From A (Agreement) to Z (z Score): A Guide to Interpreting Common Measures of Association, Agreement, Diagnostic Accuracy, Effect Size, Heterogeneity, and Reliability in Medical Research. Anesth Analg 133: 1633–1641, 2021.Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005773

- Stevens, JE, Carpenter, KJ, Eckhoff, DG, and Kohrt, WM. Quadriceps and Hamstrings Muscle Performance After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 30: 145, 2007.Available from: http://journals.lww.com/00139143-200712000-00032

- Stevens-Lapsley, JE, Balter, JE, Kohrt, WM, and Eckhoff, DG. Quadriceps and hamstrings muscle dysfunction after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468: 2460–8, 2010.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20087703

- Thomas, AC, Judd, DL, Davidson, BS, Eckhoff, DG, and Stevens-Lapsley, JE. Quadriceps/hamstrings co-activation increases early after total knee arthroplasty. Knee 21: 1115–1119, 2014.

- Uliam Kuriki, H. The Relationship Between Electromyography and Muscle Force. IntechOpen, 2012.

- Vasileiadis, D, Drosos, G, Charitoudis, G, Dontas, I, and Vlamis, J. Does preoperative physiotherapy improve outcomes in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Musculoskeletal Care 20: 487–502, 2022.

Photo Credits

- Photo Credits for images 1 and 2: Total knee replacement and Leg Anatomy - Images provided by Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

APPENDIX

Hedges-G values and descriptive statistics were calculated in R-Studio 2025.05.1 Build 513.

Muscle hedges_g lower_ci upper_ci is_significant <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> 1 A BF -1.93 -3.38 -0.483 Significant 2 A VL 1.20 0.702 1.71 Significant 3 A Vmed -2.83 -4.10 -1.57 Significant 4 BL BF -4.45 -8.04 -0.867 Significant 5 BL VL -1.23 -2.62 0.166 Not Significant 6 BL Vmed -4.45 -8.82 -0.0792 Significant 7 BR BF -5.59 -9.48 -1.70 Significant 8 BR VL -1.06 -1.92 -0.202 Significant 9 BR Vmed -3.41 -5.11 -1.72 Significant Overall Values: Muscle hedges_g lower_ci upper_ci is_significant <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> 1 BF -1.94 -2.82 -1.06 Significant 2 VL 0.0270 -0.701 0.755 Not Significant 3 Vmed -3.47 -4.62 -2.32 Significant

Descriptive Summary of Normalized EMG Values

Trial Muscle Mean SD Min Max N

<fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 Pre BF 0.265 0.0774 0.161 0.43 15

2 Post BF 0.502 0.149 0.296 0.681 15

3 Pre VL 0.462 0.0530 0.385 0.57 15

4 Post VL 0.461 0.0528 0.347 0.576 15

5 Pre Vmed 0.328 0.0493 0.241 0.422 15

6 Post Vmed 0.510 0.0528 0.424 0.621 15